Yesterday our second iOS game was submitted to Apple for approval. Hopefully it’ll be in the app store in a few days, all being well.

Way back in the early 80s what were probably some of the best and most challenging arcade games ever devised were made by Williams Electronics – games like Defender, Stargate, Sinistar – and a game which some consider to be perhaps *the* greatest pure arcade shooter ever made, Robotron.

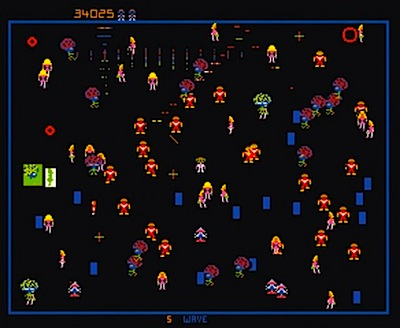

The designer of these games, a chap by the name of Eugene Jarvis, was my absolute hero back then, and his designs had a major influence on my own style of game design. My favourite of all his designs was without doubt Robotron. It took the basic idea from Stern’s Berzerk – a lone humanoid battling for survival in a maze full of killer robots – and cranked the speed and difficulty all the way up to 11, giving the player huge amounts of rapid firepower but also filling the play arena with hundreds of enemies all intent on your swift and brutal demise. A twin-stick control system allowed you to move and fire with great precision and accuracy – an absolute necessity in a game which was brutally, beautifully, sensually difficult. As in many of Jarvis’ games, an inexperienced player could expect to be obliterated within seconds of beginning a game. Only the very best and most skilful players could expect to see the far side of level 15.

As in all his games, however, despite the extreme difficulty the challenge and excitement of play was enough to make one want to put in the hours of practice to become good. All the tools were there to master the challenge if you could only develop the skills. The game was brutal but fair, and the gameplay was rewarding and exciting. As in Defender, a rescue mission was added to the basic survival gameplay, allowing skilful players to rack up big scores for rescuing beleaguered Humanoids once the basics of survival were mastered. This superlative game was presented in what was the signature style of Jarvis and his colleague Larry DeMarr – fast action, large numbers of brightly coloured enemies, and wonderful explosions that shattered the enemies into tiny pieces all over the screen when shot, all to the accompaniment of loud, burpy square-wave sound effects that were a perfect accompaniment to the frantic action.

I remember the local arcade in Newbury actually took out an ad in the local paper advertising the arrival of Robotron in the arcade, and I made a special trip with my mates to go and see the new game, emerging from the arcade some hours later and a few quid lighter, blinking and besotted.

Most of the 8-bit machines of the day weren’t really up to making a really decent and convincing version of Robotron (although there were a few damn good tries – I remember “Wild West” on the humble Speccy being a jolly good attempt at it). Most of them simply weren’t up to replicating the sheer number of onscreen enemies and fast pace of the coin-op.

With the arrival of the 16-bit machines in the mid to late 80s, however, that changed; and in 1991 I decided that I’d rather like to do a Robotron style game myself, on the Atari ST. I’d done a few shooters on the ST before that and figured that my sprite routines might be up to the task of moving enough enemies around to make a reasonable version doable.

(Actually, they weren’t. By the time I’d coded up a few levels and added the necessary explosion style, it was obvious that the game was going to be painfully slow. I almost gave up at that point, but in the end I sat down and went through my sprite code and managed to make it less rubbish, giving me back enough speed to make the game viable).

I started with the same basic idea – player in an arena beset by large numbers of hostile baddies, with a mission to survive, destroy the baddies and rescue some helpless friendlies. Me being me, though, I replaced the player character with a llama, and the Humanoids with various beasties that were to be rescued.

Given that it was to be a home game and not an arcade game I decided that it didn’t have to be *quite* as much like the school bully as the original Robotron, with its unequivocal mission to beat you up and take all your money. Robotron, despite all its awesome, lethal grace and glory, was in fact quite a shallow game – you’ve seen every enemy in it by the time you reach level 8, and from there it just gets increasingly terrifying until you run out of nerve or money. I liked the idea that a game could be a bit of a journey, and a lot of my 8-bit designs reflected that, with a large number of distinctive levels to discover and work your way through.

So in my new game, which I called “Llamatron”, I could afford to make the game not quite so brutal, and add in a slew of enemies and extra gameplay elements over a whole bunch of levels – 100 all told by the time the game was finished.

To incline things a little more in the player’s favour and make it possible for even normal, non-bionic players to achieve significant progress, various things were added: not least a series of powerups to augment the player’s already not insignificant firepower. Periodically shot enemies would release a bubble; each bubble contained some goody that would aid in the slaughter of the baddies. A smart bomb bubble when collected could destroy everything in one huge explosion and facilitate a rapid exit from a tricky level. ”Hot bullets” sliced through many enemies without being stopped by them, enabling you to slay scores of baddies in seconds. A three-way shot provided a broader arc of fire. Even the act of rescuing the beasties provided a couple of seconds of more destructive firepower.

The addition of these extras made it so that you didn’t have to be quite as super awesome a player as in Robotron to make reasonable progress, meaning even moderately skilful players could, with a bit of practice, expect to see all of the game’s 100 levels.

Perhaps the most significant addition to the game in terms of making it more accessible to mere mortals was the “AI Droid” – that’s the purple thing visible in the screenshot above. Players had the option to play the game solo or with the accompaniment of the indestructible Droid, which behaved like a little ally helping in your mission, shooting enemies and rescuing beasties for you. Beginning players found it helpful to use the Droid, allowing them to concentrate on basic beginner stuff like not walking into baddies and generally not being killed. Many people found it helpful and I received numerous letters from people who told me they’d particularly appreciated the Droid as it allowed them to play and enjoy the kind of hectic shooter which they would otherwise have found too difficult and offputting.

Populating the levels were many different kinds of enemies – not just the grunts and their cohorts from Robotron, but also a large and exotic menagerie of enemies that were typically Llamasoftian in their nature. 16 ton weights attempted to drop themselves on your beleaguered llama. Flapping toilets firing loo rolls, giant killer sheep-centipedes, arena-roaming lasers, screaming Mandelbrot sets, angry telephones, shrieking pointy arrows and goat-firing false teeth were just a few of the bizarre oddities which served to both challenge and amuse the player during his journey through the levels, eventually leading to “Herd Heaven” where the victorious llama was surrounded with nothing but a huge number of happy besotted beasties.

When the game was finished none of the normal publishers seemed interested in taking it despite my offering it to a few, and in the end I released it as shareware (true shareware, which you rarely see these days, in which you give the entire game away – the whole thing, not a feature-limited version – and only ask people to pay if they like it). Back then shareware was a realtively new idea, at least in Europe, and I wrote an extensive readme file explaining how it worked. Much to my surprise and delight it worked really well and we got a lot of registrations, nearly every one accompanied by a letter from the player saying how much they enjoyed the game and liked the idea of shareware distribution. It was a really good time and a great feeling to see the game so enthusiastically received.

I did a port to the Amiga and there was a PC port done as well and to this day many regard the game as something of a classic (as you can read here). Definitely Llamatron was the most popular thing we did on the 16 bit machines.

Anyway, that’s the history of Llamatron.

It’s always been in the back of my mind to one day do an update to Llamatron – and in fact Minotron isn’t really that update. I have ideas for a proper sequel to Llamatron which i will get around to doing one of these days, which will move the game on a bit from being a pure arena-based shooter. And I have been put off the idea of doing an arena shooter on iOS for many reasons, partly because I wasn’t sure if the controls would be up to the task, and partly because it seems that everyone and his dog is doing arena shooters these days.

However doing the first Minotaur Project game made me realise that iOS controls needn’t actually suck and that with a bit of care it might be possible to do a reasonable dual-stick style shooter on iOS; and the Minotaur Project theme itself, with its idea of doing games in the style of augmented old hardware, might allow me to have a bit of fun doing a bit of a reimagining of Llamatron whilst still allowing the game to be itself and stand apart from all the arena shooters trying to be just like Geometry Wars. So a bit over a month ago I set out to make Minotron: 2112.

In keeping with the old hardware theme I thought this time round I’d infuse the game with a bit of the old Mattel Intellivision style. Although the Inty was never quite the classic gaming powerhouse that the old 2600 VCS was, it did have its fair share of good games and I had a lot of fun back in the day playing games such as Tron Deadly Discs and the Dungeons and Dragons game that was almost like a simple Rogue-style dungeon crawl. In some aspects the Inty was graphically superior to the VCS, almost like a simplified version of the Commodore 64, with 8 monochrome sprites and a scrollable character screen that was, if I recall, 20×12 chunky characters in size.

Once loaded the title screen is a classic Inty style. I gave myself a few more characters of horizontal resolution so I could fit “Llamasoft” in there ![]() .

.

Once in-game there’s a fair bit of artistic license taken with the theme system. I decided that just using pure monochrome sprites for everything would be a bit too limiting so most of the actual pixel art in the game is either directly lifted from the Atari ST game, or done in a pretty similar style. I’ve retained that marvellous Inty font, though, and the huge characters for in-game status and score indications.

In this shot you can see the 16-ton weight hovering menacingly while the player (in Minotron the llama from Llamatron is replaced by a minotaur) gathers up beasties. The hearts over the heads of the beasties indicate that a Love powerup is in effect, which makes all the beasties run towards you.

The minotaur animation is based in part on the classic “Running Man” animation sequence – there was one animation of a little guy running that you’d see in a lot of Intellivision games. In keeping with the Inty theme various other sprites and sound effects from Inty games make cameo appearances throughout the game.

Here the player is about to collect a powerup bubble (looks like a Floyd bonus to me; hard to see as the graphic in the middle is spinning and we’re just seeing it edge on. Spinning, scaling and rotating stuff is trivially easy these days and lots of things in Minotron do it – back on the ST it would have taken a LOT of effort just to get such minor effects to happen!). The player here is in fact in shit street if that isn’t a 3-way shot powerup since all those fire hydrant generators (the purple spinny things) have all just generated fire hydrants (the blue things) which are all about to fire, so things are about to get a little hirsute.

Ah, one of my favourite powerups, Big Stompy Minotaur. Getting this powerup entumesces your minotaur to enormous size and for a few seconds he can charge around the screen with impunity, grunting and stomping and squashing the hell out of anything that gets in his way. Most satisfying, especially if triggered on a level which has been giving you some grief.

Here the angry toilet is back, firing homing toilet rolls at you along with lots of cups of tea. He’s not too hard to take out with judicious positioning and a bit of patience, but you have to be careful when he is destroyed as what emerges can be dangerous.

Here the player is attacked by multiple instances of Wales, a laser, and appropriately enough the rain. Rain was a recurring theme throughout Llamatron. Certain levels featured raindrops falling steadily from the top of the screen. In order to stop the rain and end the level the player must touch and open the umbrellas which float around the screen.

Another classic enemy making a return is the “screaming Mandy” – a glowing Mandelbrot set which floats round the screen, often firing at you, and screaming loudly whenever shot. These are a bit trickier than in Llamatron as they now acquire the velocity of the bullets with which they are shot and if you’re not careful it’s possible to send them bouncing around so fast that they come flying back and hit you! (Trivia enthusiasts may like to know that Mandy’s scream is in fact the sound of Zaphod Beeblebrox falling out of his spaceship whilst drunk, from the original Radio 4 presentation of the Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy).

Many will be curious to know how I’ve approached the issue of controls. I’ve not been overly fond of some of the arena shooter controls on iOS which can have a tendency to feel a bit overly slippery, at least for a game like this in which the player character isn’t really like the ship in Geometry Wars. In GW the ship has a fair degree of inertia and its motion is meant to be a bit slippery. In Minotron the minotaur is walking, and you need to guide him with a fair degree of precision, so the feel of his control is a lot less “inertial” than in Geom Wars.

I’m not at all a believer in “on-screen joypads” or anything like that. In fact I don’t think you need to draw anything at all on screen to actually represent the “virtual joystick”; such extra graphics just get in the way, and one of the things we need to do on iOS is do all we can to help with the inevitable issue of visibility. Simply sliding in a direction is enough to define a motion, so we can allow the controlling touch to fall anywhere. It needn’t be graphically represented on the screen at all. Your visual attention should be on the rest of the screen, not on your thumb, after all.

In considering the second control, that of aiming the shots, we have to consider that Minotron is in one important regard quite a different game from the likes of Geometry Wars, and design the control accordingly. Geometry Wars is like one continuous level, with enemies constantly appearing all around you as you play; and as such you pretty much need to be continuously altering your aim as you move to shoot at the threats as they form around you. This necessitates that you pretty much always have to have both touches engaged and active continuously as you play.

In Minotron, however, the game is divided up into discrete levels, and for the most part the enemies you see at the start of the level are all that you need to kill to progress to the next level. So it is possible to clear out sections of the screen to win ever increasing zones safe and clear of enemies as the level progresses. In doing this strafing becomes much more important than constantly swivelling the aiming of your shots. Typically you’ll aim the shots in a particular direction, then hold that fire angle as you move, mowing down swathes of enemies in a particular direction, winning clear space you can safely move into.

As such the aiming touch can be a momentary thing rather than something you need to hold down all the time. A quick swipe to aim, then you can retract the aiming thumb for better visibility, only bringing it on again to re-aim a while later. This makes for much better visibility during gameplay.

In play then you will usually have one touch held down continuously – the moving touch, with which you are constantly moving your minotaur; and one applied occasionally, the aiming touch. So, rather than separating the touches spatially – “left touch moves, right touch aims” – we separate the touches temporally. The first touch, applied and held down, becomes the moving touch. The second touch swiped periodically becomes the aiming touch. (You can still hold down the aiming touch for full-on swivelly aiming when the occasion demands it).

The advantage of this method is that it has no inherent handedness. A player who prefers to use the right thumb to move can do so by simply holding down the right thumb first; it automatically becomes the moving touch. In fact it is useful sometimes, should the action drive the minotaur under your controlling thumb, to be able to swap the handedness of the controls on the fly, which you can do easily by simply releasing and reapplying the touches.

The controls thus provide all the control necessary for playing effectively whilst being versatile with regard to handedness and optimised for best visibility.

In the original Llamatron the option for three continues was provided to allow the player some chance to push his progress onwards after he dies the first time. In Minotron I’ve incorporated something that people have liked from Gridrunner++/Revolution and Space Giraffe – the idea of Resume Best.

As you complete each level your score and number of lives left is compared with a record of your previous best. If you have more lives, or the same number of lives but a better score, a new Resume Best point for that level is saved. On subsequent games you then have the option of selecting any level you’ve reached before, and resuming your play at that level with the best lives and score that you’d had at that point previously.

This gives you the option for choosing a favourite level or two and just dipping in and trying to bump up your Resume Best for those levels rather than playing through the whole game, for those times when you just want a quick go rather than the whole journey. It also allows you to gradually build up a sort of “cumulative best game ever” over all the levels as you return to the game and improve the Resume Best scores.

There’s also Endurance Mode provided for all the main game modes, another way to have a quick game that people seemed to enjoy in Minotaur Rescue. In Endurance Mode you begin at the beginning with one life, and no extra lives are ever given. It’s up to you to stay alive for as many levels as you can, scoring as much as you are able.

There are four main game modes, which I’ve designed being mindful of how people found the AI Droid such a help in the original Llamatron. Firstly there’s Normal mode where the player plays alone. The reward for this is that more and more powerful powerups are available in this mode, and higher scores are possible.

The AI droid makes a return (several shapes are available, including a pony, although the release pony isn’t quite as explicitly a My Little Pony as this one). Just as in the original Llamatron the AI droid helps shooting baddies and collecting beasties.

There’s Hard Mode, for purists who want a game closer to the original Llamatron. This omits some of the more exuberant powerups from the updated game and is generally a bit more challenging.

Finally there is Simplified Mode. In this mode the player can play using one touch alone, with all aiming and firing being automatic, a bit like in Space Invaders Infinity Gene. This mode I have found ideal for play on the smaller screen of the iPhone in situations where you don’t want to or can’t be bothered to hold the device in both hands and use both hands to play. It’s actually quite relaxing and fun even on the iPad, and still challenging enough to be rewarding to play.

In all I hope we’ve provided enough different modes and styles of play to allow players of all calibres to enjoy playing Minotron, even those who don’t consider themselves to be all that great at shooters. The main objective is that the game should be fun for all kinds of players of all kinds of ability levels.

We’re pretty pleased with how the game’s turned out. It’s a joy on the iOS hardware platforms, and runs with a fluidity and smoothness that I could only have dreamt of back in the old Atari ST days, even when loaded with many more enemies and effects than Llamatron ever had. The pace of the game is nice, with powerups and such keeping the gameplay moving forward at a nice pace and rarely leaving the player stuck. The sound effects are loud and joyful and at times when everything’s kicking off on the iPad you can feel the whole thing vibrate in a most satisfying manner. It’s great fun to play and we hope it’ll bring back some good memories for those who loved the original Llamatron as well as providing a good old fashioned blasty good time to all who play it ![]() .

.

See you on the leaderboards!